Think you’re above average? So does everybody else.

This is the fifth in our S4 Insights series: Proving the Soft Stuff with Hard Science.

Nearly 90% of MBA students rated their academic performance as above the median in a Stanford University study. While this is mathematically impossible, it’s something we often see. Many business people struggle with self-awareness because, in order to become self-aware, we must confront our feelings. When we fail to do so, we run the risk of deceiving ourselves and others. And it’s not just business people who are prone to this.

In a similar study, 93% of US drivers put themselves above average when it comes to driving skills and safety when operating a motor vehicle.[1] What psychologists call the “illusory bias” is a product of how difficult it is to truly reflect on feedback from others. Whether we’re at the wheel of an automobile or a business, this bias can be enough to run us off the road.

This brings us to our fifth and final key to powerful business relationships: manage yourself before you manage others. And the first step to managing oneself is becoming aware of oneself.

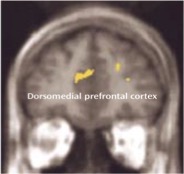

Managing yourself is profoundly more difficult than prescribing and controlling the behavior of others. In fact, you use a completely different part of your brain, the right dorso-medial prefrontal cortex, to reflect on your own emotions than you do to reflect on the emotions of others.[2] Becoming self-aware isn’t easy, but it’s certainly possible. Self-awareness is a skill that can be learned and, just like a muscle, it can be strengthened with the right exercises. Here’s how:

Take time to stop and reflect.

Emotions can alter our thinking in many ways: they can disrupt our cognition or they can prioritize our attention towards what’s important. Measures of cerebral blood flow, a marker of neural activity, show that areas of the brain functionally responsible for emotional thinking are deactivated when someone participates in a cognitive task.[3]

Figure 1: While a complicated medial paralimbic network is responsible for awareness in general, the left and right dorso-medial prefrontal cortex are unique to awareness of oneself.2

Perhaps you can remember a time when you were upset and kept yourself busy with tasks and cognitive activities to take your mind off your feelings. The part of the brain you use to reflect is being suppressed when you’re focused on work. The more conscious we are of the role our emotions play in our decision making, the better we can manage ourselves and ultimately others.

Proactively seek, listen to, and reflect on feedback from others.

Self-awareness means being clear about your strengths, limitations, hopes, emotional responses, and their impact on your behavior. The best way to achieve that clarity is through our reflection on feedback from others. But not all feedback is equal.

Seek useful feedback, something you can act on, not judgement or critiques, which often tell you what didn’t work but not what you can do to improve your approach. Regularly debrief interactions and projects. Ask for real-time feedback on your decisions and behavior. And, most importantly, take time to reflect on this feedback.

By objectively examining our own strengths and weaknesses, we are able to identify opportunities that can improve our relationships. This emotional intelligence is a primary driver of the quality of business relationships we have with other individuals, teams, and organizations. In fact, being conscious of our vulnerabilities, fears, and longings makes it easier to empathize with others who are experiencing similar feelings. Being self-aware not only will make us more effective in our business relationships, but it also will make many aspects of our lives easier and ultimately more fulfilling.

After 30 years of helping companies leverage powerful business relationships to grow and thrive, it turns out one of the most important business relationship is the one we have with ourselves.

By Trevor Thomas

Read more in this series:

- Proving the Soft Stuff with Hard Science

- Heartbeat of Your Business: Walking in Others’ Shoes

- Trust: It’s in Your Head and in Your Control

- The Power of Sharing

[1] Svenson, O. (1981). Are we all less risky and more skillful than our fellow drivers? Acta Psychologica, 47, 143-148.

[2] Fossati, P., Hevenor, S. J., Graham, S. J., Grady, C., Keightley, M. L., Craik, F., & Mayberg, H. (2003). In search of the emotional self: an fMRI study using positive and negative emotional words. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(11), 1938-1945.

[3] Drevets, W. C., & Raichle, M. E. (1998). Reciprocal suppression of regional cerebral blood flow during emotional versus higher cognitive processes: Implications for interactions between emotion and cognition. Cognition and emotion, 12(3), 353-385.