What goes on in your head when you decide to share information

This is the fourth in our S4 Insights series: Proving the Soft Stuff with Hard Science.

Power is not defined by the amount of information you store, but by the amount you are willing to supply to lift up those around you.

Expertise can be power in our hypercompetitive business world and it’s hard to escape the whoever-knows-the-most-wins mentality. Those who are successful, though, know that sharing information actually increases your personal power, not hinders it. You can draw on authority instead, but positional power will only give you short-term solutions and halfhearted compliance; personal power, on the other hand, will lead to long-term solutions and sincere commitment.

Hence, our fourth key to powerful business relationships: share information to increase personal power. But how can we orient ourselves and our organizations towards sharing and away from hoarding when it comes to critical information?

It starts by understanding what goes on in our heads when we make decisions. The better we understand the decision-making process when someone is given an opportunity to share information, the more easily we can promote an information-sharing culture in our personal and professional lives.

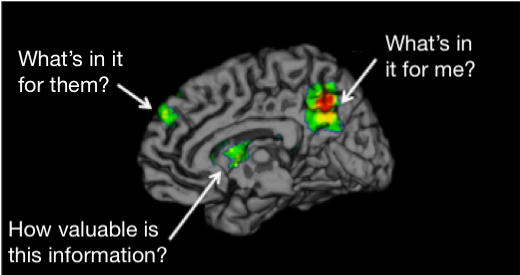

Researchers in a 2016 study were able to accurately predict whether participants would share New York Times articles based on their neural activity.1 That’s because, according to the basic neurocognitive model of information sharing, we always ask ourselves the same three questions before we decide to share information.

1. “How valuable is this information?”

One of the most common reasons why we choose not to share information is because it never occurs to us that the information is important or valuable. The brain weighs the significance of different types of information onto a common value scale that allows for direct comparisons.2

Figure 1: Neural activity in these three regions can predict whether or not you will share information.

The more quickly and confidently we can identify valuable information, the more likely we are to share it with those who need it. To encourage this, be explicit and specific about what kinds of information would be most valuable and the most helpful format in which to share it.

2. “What’s in it for me?”

Sharing information can be very time consuming and makes most people uncomfortable. It could reveal a mistake you’ve made or give someone else the chance to take credit for your ideas. Accordingly, once we have decided that a piece of information is valuable, we must decide why we should go out of our way to share it. To answer this, we weigh the personal benefits of sharing a piece of information against the costs of actually sharing it using self-referential processing.3

Reducing the costs and increasing the benefits of information sharing is a powerful way to promote this behavior. For example, establish systems that minimize the time and effort required to share information while providing incentives and recognition for colleagues and business partners who do so.

3. “What’s in it for them?”

Once we’ve decided that a piece of information is valuable and that sharing it benefits us, we think about how this information could benefit others. For this, we recruit the brain’s mentalizing system, which allows us to consider the knowledge, needs, and desires of other people.4

A cross-functional, collaborative environment is a strong facilitator of information sharing because it familiarizes people with the needs and desires of others. By facilitating openness and inclusion where you work, it becomes easier for people to know what other people know – and, more importantly, what other people want to know. This not only promotes information sharing, but it also makes sure information is only shared with the people who need it.

Using the personal power we generate by sharing information, we can develop resilient business relationships that enrich our careers and ensure our long-term success. Not only that, but sharing information allows us to harness the power of collective genius and could take your business to the next level. Power is no longer simply defined by the amount of information you store, but by the amount you are willing to supply to lift up those around you.

By Trevor Thomas

Read more in this series:

- Proving the Soft Stuff with Hard Science

- Heartbeat of Your Business: Walking in Others’ Shoes

- Trust: It’s in Your Head and in Your Control

- Scholz, C., Baek, E. C., O’Donnell, M. B., Kim, H. S., Cappella, J. N., & Falk, E. B. (2017). A neural model of valuation and information virality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 201615259.

- Bartra, O., McGuire, J. T., & Kable, J. W. (2013). The valuation system: a coordinate-based meta-analysis of BOLD fMRI experiments examining neural correlates of subjective value.Neuroimage,76, 412-427.

- Falk, E. B. (2013). Can neuroscience advance our understanding of core questions in Communication Studies? An overview of Communication Neuroscience. Communication@ the Center, 77-94.

- Dufour, N., Redcay, E., Young, L., Mavros, P. L., Moran, J. M., Triantafyllou, C., … Saxe, R. (2013). Similar brain activation during false belief tasks in a large sample of adults with and without autism. PLoS ONE, 8(9), e75468. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075468